Forest guard women patrol

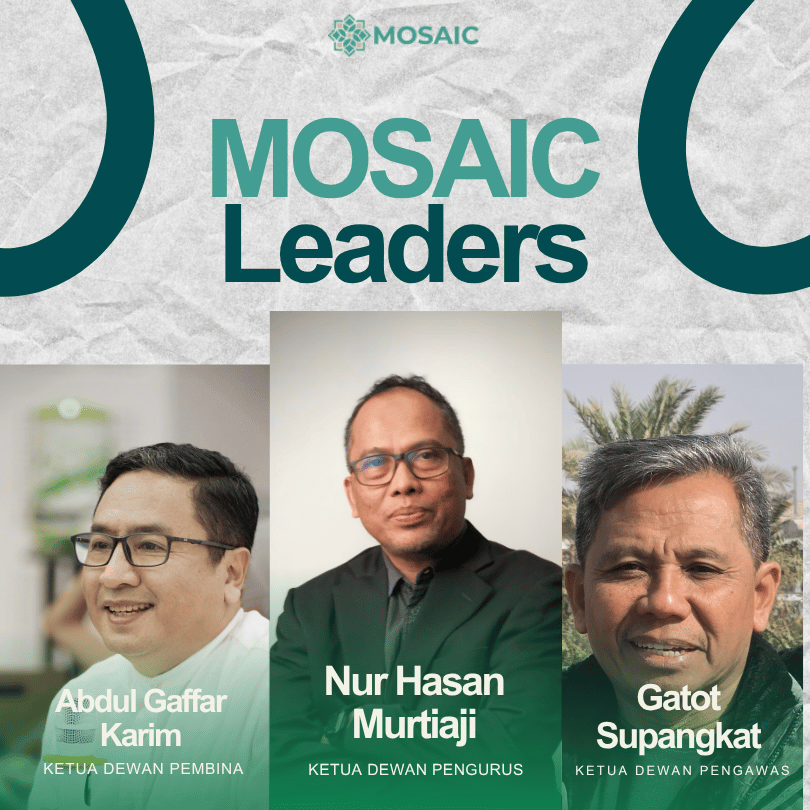

Sumini, a resident of Damanbaru, Aceh, decided to form a patrol team to guard the forest.

MOSAIC-INDONESIA.COM, JAKARTA -- As a vast tropical island nation stretching across the equator, Indonesia is home to the third largest rainforest in the world, with a diverse array of endangered wildlife and plants, including orangutans, elephants, and giant forest flowers. Some species even exist only in Indonesia.

Since 1950, more than 285,715 square miles (740,000 square kilometers) of Indonesian rainforest -- twice the area of Germany -- have been cut down, burned or altered for the development of palm oil plantations, paper and rubber, nickel mining and other commodities, according to Global Forest Watch.

The Associated Press reports, in recent years, deforestation has slowed, but has continued. Some women in from one province have formed patrols to protect against deforestation. The idea to carry out these patrols came after a village in Aceh was forced to evacuate due to flash floods exacerbated by deforestation.

In Damaran Baru, which borders one of Southeast Asia's richest tropical rainforests, many villagers depend on forests for their livelihoods. The farmers harvest coffee from bushes on the slopes of the mountain. Meanwhile, water flows from the mountain slopes which serve as a source of water for drinking and cooking the villagers.

The occurrence of deforestation practices as a result of irresponsible agricultural practices and misuse of forest resources. The practice has very bad consequences, said Sumini, a villager in Aceh.

In 2015, heavy rains triggered flash floods in the village. The disaster forced hundreds of people to evacuate. When the water receded, Sumini went into the forest. He watched as watersheds strewn with trees had been illegally cut down. “I looked at it and thought, 'This is what caused the landslides and disasters, '” Sumini said in an interview.

She also thought about creating a forest patrol system that women would practice: “As women, what do we want to do? Do we have to be silent? Or can we not get involved?”

Indonesia has rangers in its national parks, and a number of watchdog groups elsewhere, including some indigenous groups. But Sumini's idea is classified as new.

After lobbying women in the village to start patrols, Sumini got rejection from a province that is traditionally patriarchal and governed under Islamic law, known as Sharia. But after convincing village leaders and husbands of interested women — including allowing men to accompany them on patrol — Sumini was granted permission to form the group.

Sumini began working with the Aceh Forest, Nature and Environment Foundation to help register the patrol group officially with a social forestry permit -- a formal government-backed permit that allows local communities to manage their forests.

After permits are processed, the foundation begins teaching standard methods of forest conservation to prospective rangers, said Farwiza Farhan, one of the founder. The first training, he said, was to learn to read maps and teach other standard methods of forestry, such as recognizing wildlife signs and using GPS.

“The way outsiders explore the forest is very different from that of local people. They know, but not necessarily translated into the standard language we use, like maps and GPS,” Farhan said. “Finding and creating spaces where we speak the same language when talking about forests is key.”

In January 2020, the group conducted their first official patrol. Since then, their monthly trips across the forest include mapping and monitoring tree cover, cataloging endemic plants, and working with farmers to replant trees. They periodically measure each tree and mark its location, marking it with warning tape not to cut it down. When they see someone in the forest, they remind the person of the importance of the forest to their village and give them seeds to plant.

Sumini said the simple tactics women use, as opposed to abusive confrontations, are more effective in getting society to change their habits. They carried no weapons, other than large knives which they used to break through the forest when necessary, but showed no fear for their own safety. Violence in the forest almost never occurs, and the number of guards usually exceeds the number they encounter. Women do not have the authority to arrest people, but they can report to the authorities.

Over the years, Muhammad Saleh, 50, burned parts of the forest. Not only that, Saleh hunts tigers that he can kill. He sold it to help feed his family. The civil war that raged at the time had hurt the local economy. Each tiger will earn about 1,250 US Dollars. On other days, he felled trees to be used as firewood or trapped birds for sale at the market. His wife, Rosita, 44, begged him not to leave. She reminds him of the animals that will be affected by his actions.

It took years for Saleh to become aware of the message from his wife. On one day, Saleh decided to stop hunting and cut down trees. He began to join his wife patrolling the woods. He said he had noticed progress since starting the patrol. The forest has more birds because of its denser tree cover. “Our forests are no longer deforested. The animals are awake and we are getting more and more awake,” he said. “The whole world is feeling the impact, not just us.”

Now the methods used by forest rangers are being applied elsewhere in Indonesia, along with local organizations, non-governmental organizations, and international foundations that help bring together female-led forestry groups.

Members of the Aceh group have met with women from provinces across Indonesia that are severely affected by deforestation. They share information about prominent local forestry programs. They also teach the public how to participate in wilderness mapping, how to draft proposals and apply for forestry management permits and how to demand better enforcement of laws against poaching, mining and illegal logging. “There is now more connectivity between mothers, grandmothers, and wives to talk about how to overcome problems and be environmental warriors,” Farhan said.

Women's focus on forest management is crucial to the success of social forestry programs, said Rahpriyanto Alam Surya Putra, director of The Asia Foundation's environmental governance program in Indonesia, who has helped organize meetings between female-led groups.

A survey of 1,865 households conducted by the foundation found that when women were involved in community forest management, this would increase household income and more sustainable forest governance. But female-led forestry management still faces challenges in Indonesia, she said. Some communities that have traditionally been patriarchal are less understanding of the benefits of women's participation. Even when women are empowered to engage in forestry, they are still expected to take care of household chores and children.

Nevertheless, women forest rangers in Damaran Baru say that the positive impact they have made has motivated them to continue their work for future generations. “I'm inviting other mothers to teach their children and communities about the forest as we have... we want them to protect it,” she said. “Because if the forest stays green, the people stay prosperous.”