80 GW solar power plant for 80 thousands villages, could it be possible?

National banks do not yet have a specific risk scheme for village energy projects.

MOSAIC-INDONESIA.COM — Clean energy appears to have momentum after President Prabowo Subianto announced plans to build 80 GW of solar power plants (PLTS) across 80,000 villages in Indonesia. The President has even ordered Danantara to develop a prototype for solar-based rural electrification.

The funding required for this power plant development — part of the 100 GW Energy Self-Sufficiency Project — is notably high. The government, through Coordinating Minister for Food Affairs Zulkifli Hasan, previously mentioned budget US$100 billion, equivalent to Rp 1,627 trillion, to realize the program. The minister so called Zulhas estimated that the project would receive subsidies during its first four years. Afterward, villages would be expected to finance it independently from the fifth year onward.

The PLTS development plan, set to begin in 2026, is expected to:

- Provide villages with access to affordable energy

- Reduce operational costs for MSMEs (Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises)

- Strengthen agricultural and fishery supply chains

- Boost local economic productivity through solar energy applications such as cold storage, crop drying, rural transportation, and other small-scale industrial activities.

Global Solar Panel Price Decline Presents Opportunity

An article which is titled “Spotlight on Village-Level Energy Self-Sufficiency Ambitions,” published by Indonesia Cerah, reveals a global momentum of declining solar panel prices. This drop is expected to directly reduce the cost of building village-scale PLTS.

For this program, Indonesia is estimated to require an initial investment of US$100 billion (Rp 1,650 trillion, assuming an exchange rate of Rp 16,500 per US dollar). If battery storage is added, the cost would reach around US$250 billion (Rp 4,125 trillion). These figures are significantly cheaper compared to 2024 prices, when developing 1 MW of PLTS required an investment of US$900,000 (Rp 14.58 billion).

However, these amounts remain enormous for villages compared to the average annual village fund allocation of around Rp 1 billion. Meanwhile, financing through the Koperasi Desa Merah Putih (KDMP) program only offers a loan ceiling from banks of about Rp 3 billion over 6 years.

According to the analysis, village-scale energy projects based on KDMP face structural financing challenges because access to financing for small-scale renewable energy in villages remains very limited. An energy study revealed that renewable energy projects with a capacity below 10 MW struggle to secure bank loans, as project development costs can reach 120% of the total loan requested.

Currently, renewable energy financing is generally accessed by large companies with the credibility to undertake large-scale projects. This indicates that the focus on a project’s bankability tends to disadvantage MSMEs. As a result, renewable energy projects that successfully obtain funding usually have high installed capacity and large-scale development.

Village energy projects typically rely only on limited domestic funding. This situation is further complicated by Indonesia’s financial market, which is dominated by banks offering an average loan tenor of only 8 years, while energy investments require long-term financing. Another issue is that national banks do not yet have a specific risk scheme for village energy projects, unlike utility-scale projects, which have measurable technical standards and risks.

Proposal for Community-Based Independent Management

The Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) has proposed that the government’s planned 100 GW solar power plant (PLTS) project can be managed independently by village communities. IESR Electricity and Renewable Energy Analyst Alvin Putra stated that the management scheme is key to the success of the 100 GW PLTS project.

Many village electrification and centralized PLTS projects ultimately prove unsustainable and are abandoned. IESR suggests that the management of the 100 GW PLTS be handled by village communities to ensure the sustainability of this large-scale program targeting 80,000 villages.“This also reflects the community’s aspiration — why these projects are not sustainable,” said Alvin.

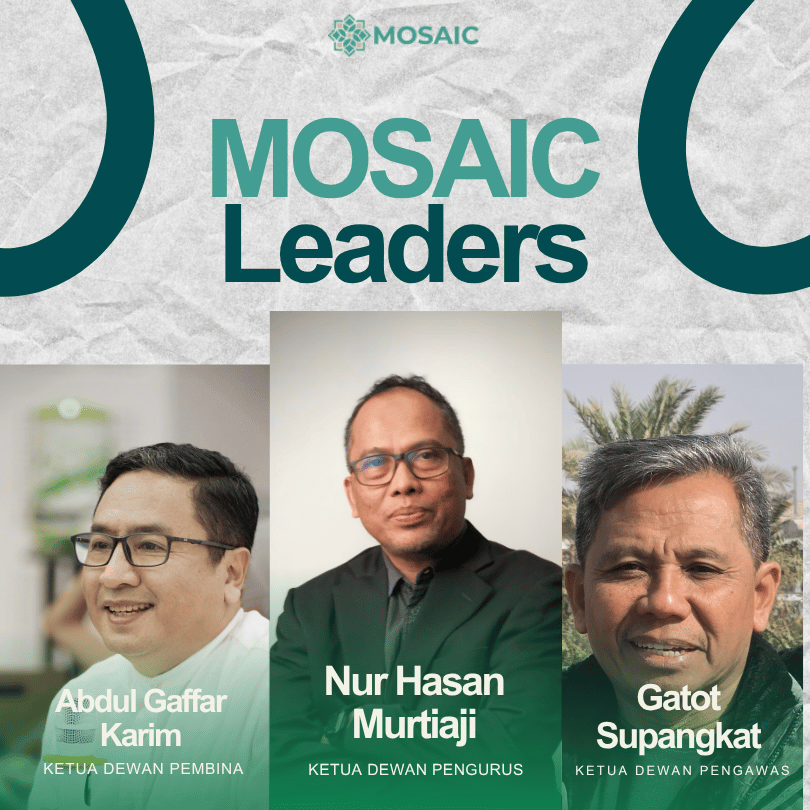

Lihat postingan ini di Instagram

IESR further recommends that each village manage its PLTS project as an independent energy enterprise using an off-grid scheme. Under this approach, the power plant would operate independently without connection to the state electricity company (PLN)’s grid.

“Conceptually, we see an opportunity here — it can be managed off-grid. Because we know that PLTS is actually very flexible,” Alvin explained.

Project management could be entrusted to local entities such as cooperatives or Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDes). In remote areas, PLTS is considered more economical and environmentally friendly compared to the diesel generators currently in use.

Beyond ensuring energy availability, the self-management scheme is also seen as having the potential to create new job opportunities for local communities. Residents could be trained as operators and project management team members, thereby empowering the village economy and building local institutional capacity.